Vertical Slice Architecture

INFO

This guide is written from the standpoint of a CQRS Architecture. While we think a vertical slice architecture (VSA) could be valuable otherwise, vertical slices and CQRS are a very natural pairing.

And also, we think the full "Critter Stack" of Wolverine + Marten is a killer combination for a very robust and productive development experience using CQRS with Event Sourcing.

Wolverine is well suited for a "Vertical Slice Architecture" approach where, to over simplify things a bit, you generally try to organize code by feature or use case rather than by horizontal technical layering. Most of the content about "Vertical Slice Architecture" practices in the .NET ecosystem involve the MediatR framework. It's important to note that while you can use Wolverine as "just" a mediator tool and a drop in replacement for MediatR, we feel that you'll achieve better results, more testable code, and far simpler code over all by instead leaning into Wolverine capabilities.

TIP

See Wolverine for MediatR User for more information about moving from MediatR to Wolverine.

Wolverine's Philosophy toward Vertical Slice Architecture

Alright, before we potentially make you angry by trashing the current Clean/Onion Architecture approach that's rampant in the .NET ecosystem, let's talk about what the Wolverine community thinks is important for achieving good results in a long lived, complex software system.

Effective test coverage is paramount for sustainable development. More than layering schemes or the right abstractions or code structure, we believe that effective automated test coverage does much more to enable sustainable development of a system over time. And by "effective" test coverage, we mean an automated test suite that's subjectively fast, reliable, and has enough coverage that you feel like it's not risky to change the system code. Designing for testability is a huge topic in its own right, but let's just say for now that step one is having your business or workflow logic largely decoupled from infrastructure concerns. It's also very helpful to purposely choose technologies that are better behaved in integration testing and have a solid local Docker story.

The code is easy to reason about. It's relatively easy to identify the system inputs and follow the processing to understand the relationship between system inputs and the effects of those inputs including changes to the database, calls to other systems, or messages raised by those inputs. We've seen too many enterprise systems that suffer from bugs partially because it's just too hard to understand where to make logical changes or to understand what unintended consequences might pop up. We've also seen applications with very poor performance due to how the application interacted with its underlying database(s), and inevitably that problem is partially caused by excessive layering making it hard to understand how the system is really using the database.

Ease of iteration. Some technologies and development techniques allow for much easier iteration and adaptation than other tools that might be much more effective as a "write once" approach. For example, using a document database approach leads to easier evolutionary changes of persisted types than an ORM would. And an ORM would lead to easier evolution than writing SQL by hand.

Modularity between features. Technologies change over time, and there's always going to be a reason to want to upgrade your current dependencies or even replace dependencies. Our experience in large enterprise systems is that the only things that really make it easier to upgrade technologies are effective test coverage to reduce risk and the ability to upgrade part of the system at a time instead of having to upgrade an entire technical layer of an entire system. This might very well push you toward a micro-service or modular monolith approach, but we think that the vertical slice architecture approach is helpful in all cases as well.

So now let's talk about how the recommended Wolverine approach will very much differ from a layered Clean/Onion Architecture approach or really any modern Ports and Adapters approach that emphasizes abstractions and layers for loose coupling.

We're big, big fans of the A Frame Architecture idea for code organization to promote testability without just throwing in oodles of abstractions and mock objects everywhere (like what happens in many Clean Architecture codebases). Wolverine's "compound handler" feature, its transactional middleware, and its cascading message feature are all examples of built in support for "A-Frame" structures.

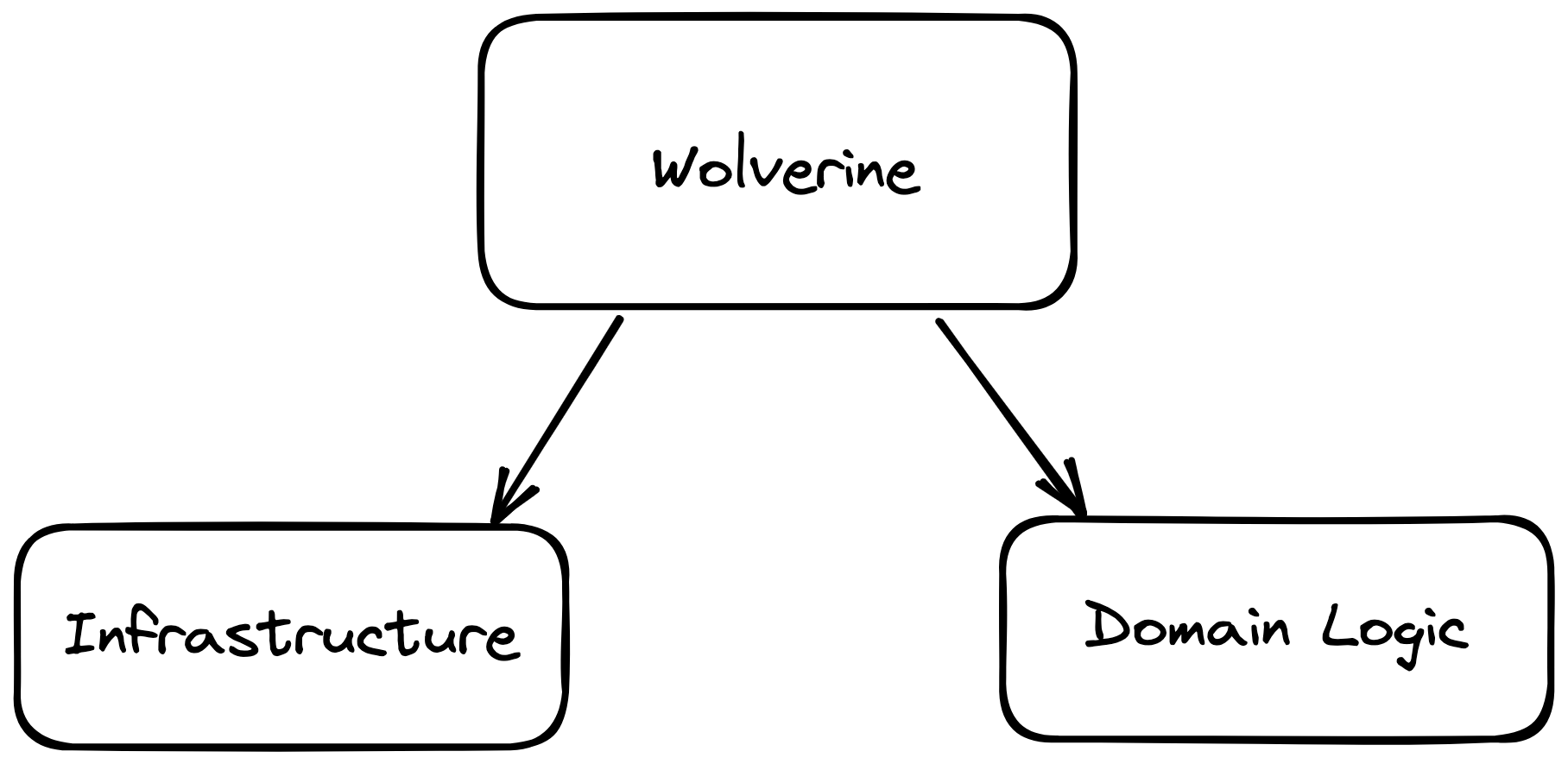

With the "A-Frame Architecture" approach, you're trying to isolate behavioral logic from infrastructure by more or less dividing the world up into three kinds of responsibilities in code:

- Actual business logic that makes decisions and decides how to change the state of the application or what next steps to take

- Infrastructure services. For example, persistence tools like EF Core's

DbContextor service gateways to outside web services - Coordination or controller logic sitting on top that's delegating to both the infrastructure and business logic code, but keeping those two areas of the code separate

For more background on the thinking behind the "A Frame Architecture" (which like "Vertical Slice Architecture", is more about code organization than architecture), we'll recommend:

- Jeremy's post from 2023 about the A-Frame Architecture with Wolverine

- Object Role Stereotypes by Jeremy from the old MSDN Magazine. That article focuses on Object Oriented Programming, but the basic concept applies equally to the functional decomposition that Wolverine + the "A-Frame" leans toward.

- A Brief Tour of Responsibility-Driven Design by Rebecca Wirfs-Brock -- and again, it's focused on OOP, but we think the concepts apply equally to just using functions or methods too

For the most part, Wolverine should enable you to make most handler or HTTP methods be pure functions.

We're more or less going to recommend against wrapping your persistence tooling like Marten or EF Core with any kind of repository abstractions and mostly just utilize their APIs directly in your handlers or HTTP endpoint methods. We believe the "A-Frame Architecture" approach mitigates any important coupling between business or workflow logic and infrastructure.

The "specification" pattern or really even just reusable helper methods from outside of a vertical slice can be used to avoid duplication of complex query logic, but for the most part, we find it helpful to see queries that are directly related to a vertical slice in the same code file. Which if you're reading this guide, you hopefully see how to do so without actually making business logic coupled to infrastructure even if data access and business logic appears in the same code file or even the same handler type.

Do utilize Wolverine's side effect model and cascading message support to be able to get to pure functions in your handlers.

Enough navel gazing, show me code already!

Let's just jump into a couple simple examples. First, let's say you're building a message handler that processes a PlaceOrder command. With this example, I'm going to use Marten for object persistence, but it's just not that different with Wolverine's EF Core or RavenDb integration.

I'll do that in a single C# file named PlaceOrder.cs:

public record PlaceOrder(string OrderId, string CustomerId, decimal Amount);

public class Order

{

public string Id { get; set; }

public string CustomerId { get; set; }

public decimal Amount { get; set; }

public class Validator : AbstractValidator<PlaceOrder>

{

public Validator()

{

RuleFor(x => x.OrderId).ShouldNotBeNull();

RuleFor(x => x.CustomerId).ShouldNotBeNull();

RuleFor(x => x.Amount).ShouldNotBeNull();

}

}

}

public static class PlaceOrderHandler

{

// Transaction Script style

// I'm assuming the usage of transactional middleware

// to actually call IDocumentSession.SaveChangesAsync()

public static void Handle(

PlaceOrder command,

IDocumentSession session)

{

var order = new Order

{

Id = command.OrderId,

CustomerId = command.CustomerId,

Amount = command.Amount

};

session.Store(order);

}

}For the first pass, I'm using a very simple transaction script approach that just mixes in the Marten IDocumentSession (basically the equivalent to an EF Core DbContext) right in the behavioral code. For very simplistic cases, this is probably just fine, especially if the interfaces for the infrastructure are easily "mockable" to substitute out in isolated, solitary unit tests. Or if you happen to be using infrastructure like Marten that has is relatively friendly to "sociable" integration testing.

TIP

See Martin Fowler's Unit Test write up for a discussion of "solitary vs sociable" tests.

A couple other things to note about the code sample above:

- You'll notice that the method is synchronous and doesn't call into

IDocument.SaveChangesAsync()to commit the implied unit of work. I'm assuming that's happening by utilizing Wolverine's transactional middleware approach that happily works for Marten, EF Core, and RavenDb at the time of this writing. - There's a Fluent Validation validator up there, but I didn't directly use it, because I'm assuming the usage of the Fluent Validation middleware package that comes in a Wolverine extension Nuget.

- I didn't utilize any kind of repository abstraction around the raw Marten

IDocumentSession. Much more on this below, but my value judgement is that the simpler code is more important than worrying about swapping out the persistence tooling later.

A "transaction script" style isn't going to be applicable in every case, so let's look to decouple that handler completely from Marten and make it a "pure function" that's a little easier to get into a unit test by leveraging some of Wolverine's "special sauce":

public static class PlaceOrderHandler

{

public static Insert<Order> Handle(PlaceOrder command)

{

var order = new Order

{

Id = command.OrderId,

CustomerId = command.CustomerId,

Amount = command.Amount

};

return Storage.Insert(order);

}

}The Insert<T> is one of Wolverine's Storage Side Effect types that can help you specify persistence actions as side effects from message or HTTP endpoint handlers without actually having to couple the handler or HTTP endpoint methods to persistence tooling or even their abstractions. With this being a "pure function", we can walk right up to it and test its functionality with a simple little unit test like so (using xUnit.Net):

[Fact]

public void handling_place_order_creates_new_order()

{

// Look Ma, no mocks anywhere in sight!

var command = new PlaceOrder("111", "222", 100.23M);

var action = PlaceOrderHandler.Handle(command);

action.Entity.Id.ShouldBe(command.OrderId);

action.Entity.CustomerId.ShouldBe(command.CustomerId);

action.Entity.Amount.ShouldBe(command.Amount);

}If you'll notice, we didn't use any further database abstractions, we didn't create umpteen separate Clean/Onion Architecture projects for each and every technical layer, and we also didn't use any mock objects whatsoever to test the code. We just walked right up and called a method with its input and measured its expected outputs. Testability and simplicity FTW!

Now, let's try a little more complex sample to cancel an order, and get into HTTP endpoints while we're at it. This time around, let's say that the CancelOrder command should do nothing if the order doesn't exist, or if it has already been shipped. Otherwise, we should delete the order and publish a OrderCancelled domain event to be handled by other modules in the system or to notify other, external systems. Again, starting with a transaction script approach first, we could have this code:

public record CancelOrder(string OrderId);

public record OrderCancelled(string OrderId);

public static class CancelOrderHandler

{

public static async Task Handle(

CancelOrder command,

IDocumentSession session,

IMessageBus messageBus,

CancellationToken token)

{

var order = await session.LoadAsync<Order>(command.OrderId, token);

// You should probably log something at the least here

if (order == null) return;

if (order.HasShipped) return;

// Maybe it's a soft delete here?

session.Delete(order);

// Publish a domain event to let other things in the system know to

// take actions to stop shipping, inventory, who knows what

await messageBus.PublishAsync(new OrderCancelled(command.OrderId));

}

}Now, to hook this up to HTTP, we could delegate to Wolverine as a mediator tool as is common in the .NET ecosystem today, either directly in the Program file:

app.MapPost("/api/orders/cancel", (CancelOrder command, IMessageBus bus, CancellationToken token) => bus.InvokeAsync(command, token));But since the Program file would get absolutely overrun with a lot of unrelated forwarding calls to Wolverine's IMessageBus entry point, and the ugliness would be much worse when you remember how much extra code you would add for OpenAPI metadata. There's no kind of automatic discovery for Minimal API like there is for MVC Core (or MediatR or Wolverine itself of course), so you might have to resort to extra mechanisms in the same file just to register the Minimal API endpoints or give up and toss in an MVC Core controller just to delegate to Wolverine as a "Mediator".

But wait, there's more! You probably want to give your HTTP API's clients some decent response to explain when and why a request to cancel an order was rejected. The Minimal API IResult gives you an easy way to do that, so we could have our Wolverine return an IResult result something like this:

public static class CancelOrderHandler

{

public static async Task<IResult> Handle(

CancelOrder command,

IDocumentSession session,

IMessageBus messageBus,

CancellationToken token)

{

var order = await session.LoadAsync<Order>(command.OrderId, token);

// return a 404 if the order doesn't exist

if (order == null) return Results.NotFound();

// return a 400 with a description of why the order could not be cancelled

if (order.HasShipped) return Results.BadRequest("Order has already been shipped");

// Maybe it's a soft delete here?

session.Delete(order);

// Publish a domain event to let other things in the system know to

// take actions to stop shipping, inventory, who knows what

await messageBus.PublishAsync(new OrderCancelled(command.OrderId));

return Results.Ok();

}

}and change the Minimal API call to:

app.MapPost("/api/orders/cancel", (CancelOrder command, IMessageBus bus, CancellationToken token) => bus.InvokeAsync<IResult>(command, token));Now, the IResult return type by itself is a bit of a "mystery meat" response that could mean anything, so Minimal API can't glean any useful OpenAPI metadata from that, so you'd have to chain some extra code behind the call to MapPost() just to add OpenAPI declarations. That's tedious noise code.

Let's instead introduce Wolverine.HTTP endpoints instead and rewrite the cancel order process -- this time with a route value instead of the request body -- to simplify the code:

public static class CancelOrderEndpoint

{

public static ProblemDetails Validate(Order order)

{

return order.HasShipped

? new ProblemDetails { Status = 400, Detail = "Order has already shipped" }

// It's all good, just keep going!

: WolverineContinue.NoProblems;

}

[WolverinePost("/api/orders/cancel/id"), EmptyResponse]

public static (Delete<Order>, OrderCancelled) Post([Entity] Order order)

{

return (Storage.Delete(order), new OrderCancelled(order.Id));

}

}And there's admittedly a bit to unpack here:

- The

[EmptyResponse]attribute is a Wolverine thing that tells Wolverine.HTTP that the endpoint produces no response, so Wolverine emits a 204 status code for empty response, and "knows" that none of the return values should be used as the HTTP response body - The

Validate()method is an example of Compound Handlers (this applies equally to Wolverine HTTP endpoints) in Wolverine, and will be called before the main method. By returning aProblemDetailstype from that method, that tells Wolverine that the method might stop all other processing by returning, well, problems. Learn more about how Wolverine.HTTP uses the ProblemDetails response type. Arguably, this is a built in form of Railway Programming in Wolverine (or at least a similar concept), but without the ugly high code ceremony that comes with Railway Programming. An idiom with Wolverine development is to largely utilizeValidatemethods to make the main handler or endpoint method be for the "Happy Path". - It's legal to return .NET tuple values from either message handler or HTTP endpoint methods, with Wolverine treating each "return value" independently

- The

Delete<Order>return type is a known persistence "side effect" by Wolverine, so it "knows" to use that to delegate to the configured persistence tooling for theOrderentity, which in this sample application is Marten. For EF Core, Wolverine is smart enough to use the correctDbContextfor the entity type if you are using multipleDbContexttypes. - In this case, because of the

[EmptyResponse]declaration, any return value that doesn't have any other special handling is considered to be a cascading message and Wolverine pretty well treats it the same as if you'd calledIMessageBus.PublishAsync(). We highly recommend using the cascading message signature instead of directly invokingIMessageBus.PublishAsync()as a way to simplify your code, keep your handler/endpoint methods "pure functions" whenever possible, and also to make the code more declarative about the side effects that happen as a result of system inputs - The

[Entity]attribute is a persistence helper in Wolverine. Wolverine is actually generating code using your persistence tooling (Marten in this case, but EF Core and RavenDb are also supported) to load the order using the "id" route argument from Marten'sIDocumentSessionservice and passing it into both the main method and theValidate()method. By default, the[Entity]value is considered to be "Required", so if the entity is not found, it will stop all other processing and return a 404 status code. No other code is necessary.

Whew, but wait, there's more! Let's say that you've opted to use Wolverine's transactional outbox integration, and for now, let's assume that you're just using local queues with this configuration in your Program file:

builder.Host.UseWolverine(opts =>

{

// Other Wolverine configuration...

opts.Policies.AutoApplyTransactions();

opts.Policies.UseDurableLocalQueues();

});and for Marten:

builder.Services.AddMarten(opts =>

{

// Marten configuration...

})

// This adds Marten integration

// and PostgreSQL backed message persistence

// to Wolverine in this application

.IntegrateWithWolverine();INFO

Wolverine makes no distinction between "events" and "commands". It's all a message to Wolverine. "Event vs command" is strictly a logical role in Wolverine usage.

In this case, the outgoing OrderCancelled event message will happen durably through Wolverine's transactional inbox (just to be technical, the local queues when durable go through the inbox storage). This is a really important detail because it means that the event processing won't be lost if the process happens to crash in between processing the initial HTTP POST and the event message being processed through the queue because Wolverine can recover that work in a process restart or "fail" the message over to being processed by another active application node. Moreover, Wolverine local queues can use Wolverine's error handling policies for retry loops, scheduled retries, or even circuit breakers if there are too many failures. The point here is that Wolverine is very suitable for creating resilient systems even with that low code ceremony model.

One last point, not only is the Wolverine.HTTP approach simpler than the commonly used Minimal API delegating to a Mediator approach, there's a couple other benefits that are worth calling out:

- Wolverine.HTTP has its own built in discovery for endpoints and routes, so you don't need to rig up your own discovery mechanisms like folks do in common "Vertical Slice Architecture with Minimal API and MediatR" approaches

- Wolverine.HTTP tries really hard to glean OpenAPI metadata off of the type signatures of endpoint methods and the applied middleware like the

Validatemethod up above. This will lead to spending less time decorating your code with OpenAPI metadata attributes or Minimal API fluent interface calls

Recommended Layout

TIP

You might want to keep message contract types that are shared across modules or applications in separate libraries for sharing. In that case we've used the message handler or endpoint class name as the file name.

You'll of course have your own preferences, but JasperFx Software clients have had success by generally naming a file after the command or query message, even for HTTP endpoints. So a PlaceOrder.cs file might contain:

- The

PlaceOrdercommand or HTTP request body type itself - If using one of the Fluent Validation integrations, maybe a

Validatorclass that's just an inner type ofPlaceOrder, but the point is to just keep it in the same file - The actual

PlaceOrderHandlerorPlaceOrderEndpointfor HTTP endpoints

And honestly, that's it for many cases. I would of course place closely related command/event/http messages or handlers in the same namespace. That's the easy part, so let's move on to what might be controversial. Let's step into a quick, simplistic example that's using Marten for persistence:

Or for an HTTP endpoint, just swap out PlaceOrderHandler for this:

public static class PlaceOrderEndpoint

{

[WolverinePost("/api/orders/place")]

public static void Post(

PlaceOrder command,

IDocumentSession session)

{

var order = new Order

{

Id = command.OrderId,

CustomerId = command.CustomerId,

Amount = command.Amount

};

session.Store(order);

}

}We feel like it's much more important and common to need to reason about a single system input at one time than it ever is to need to reason about the entire data access layer or even the entire domain logic layer at one time. To that end the Wolverine team recommends putting any data access code that is only germane to one vertical slice directly into the vertical slice code as a default approach. To be blunt, we are recommending that you largely forgo wrapping any kind of repository abstractions around your persistence tooling, but instead, purposely seek to shrink down the call stack depth (how deep do you go in a handler calling service A that calls service B that might call repository C that uses persistence tool D to...).

What about the query side?

We admittedly don't have nearly as much to say about using Wolverine on the query side, but here are our rough recommendations:

- If you are able and willing to use Wolverine.HTTP, do not use Wolverine as a "mediator" underneath

GETquery handlers. We realize that is a very common approach for teams that use ASP.Net MVC Core or Minimal API with MediatR, but we believe that is just unnecessary complexity and that will cause you to write more code to satisfy OpenAPI needs - We would probably just use the application's raw persistence tooling directly in

GETendpoint methods and depend on integration testing for the query handlers -- maybe through Alba specifications.