Runtime Architecture

INFO

Wolverine makes absolutely no differentiation between logical events and commands within your system. To Wolverine, everything is just a message.

The two key parts of a Wolverine application are messages:

// A "command" message

public record DebitAccount(long AccountId, decimal Amount);

// An "event" message

public record AccountOverdrawn(long AccountId);And the message handling code for the messages, which in Wolverine's case just means a function or method that accepts the message type as its first argument like so:

public static class DebitAccountHandler

{

public static void Handle(DebitAccount account)

{

Console.WriteLine($"I'm supposed to debit {account.Amount} from account {account.AccountId}");

}

}Invoking a Message Inline

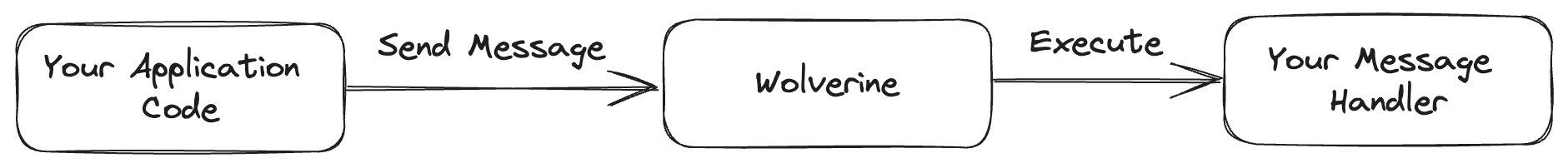

At runtime, you can use Wolverine to invoke the message handling for a message inline in the current executing thread with Wolverine effectively acting as a mediator:

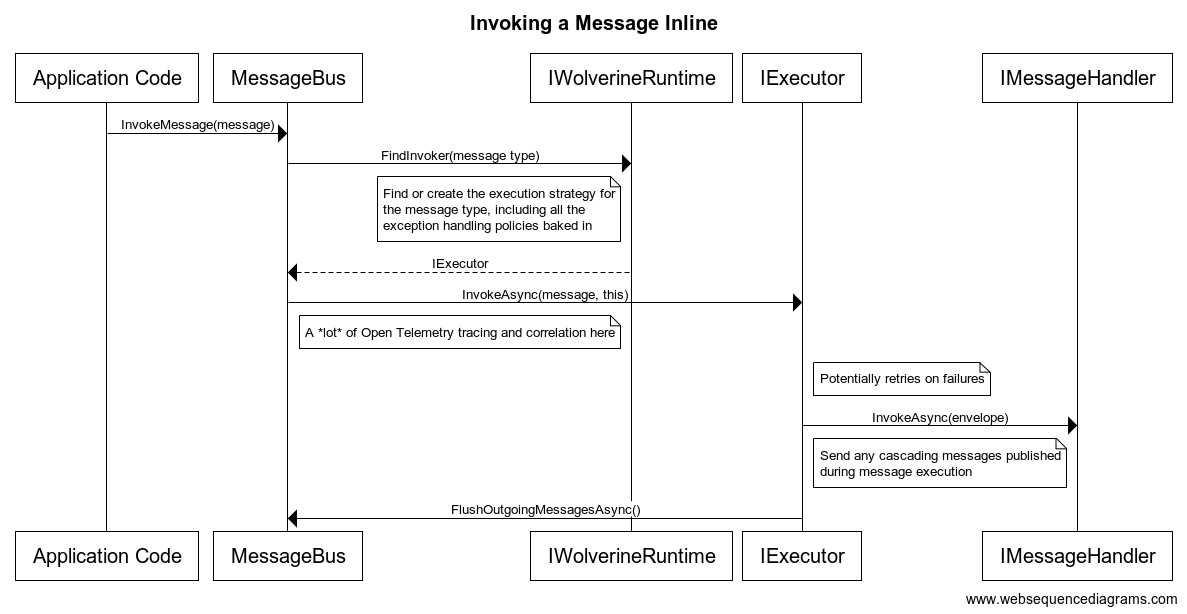

It's a bit more complicated than that though, as the inline invocation looks like this simplified sequence diagram:

As you can hopefully see, even the inline invocation is adding some value beyond merely "mediating" between the caller and the actual message handler by:

- Wrapping Open Telemetry tracing and execution metrics around the execution

- Correlating the execution in logs to the original calling activity

- Providing some inline retry error handling policies for transient errors

- Publishing cascading messages from the message execution only after the execution succeeds as an in memory outbox

Asynchronous Messaging

INFO

You can, of course, happily publish messages to an external queue and consume those very same messages later in the same process.

Wolverine supports asynchronous messaging through both its local, in-process queueing mechanism and through external messaging brokers like Kafka, Rabbit MQ, Azure Service Bus, or Amazon SQS. The local queueing is a valuable way to add background processing to a system, and can even be durably backed by a database with full-blown transactional inbox/outbox support to retain in process work across unexpected system shutdowns or restarts. What the local queue cannot do is share work across a cluster of running nodes. In other words, you will have to use external messaging brokers to achieve any kind of competing consumer work sharing for better scalability.

INFO

Wolverine listening agents all support competing consumers out of the box for work distribution across a node cluster -- unless you are purposely opting into strictly ordered listeners where only one node is allowed to handle messages from a given queue or subscription.

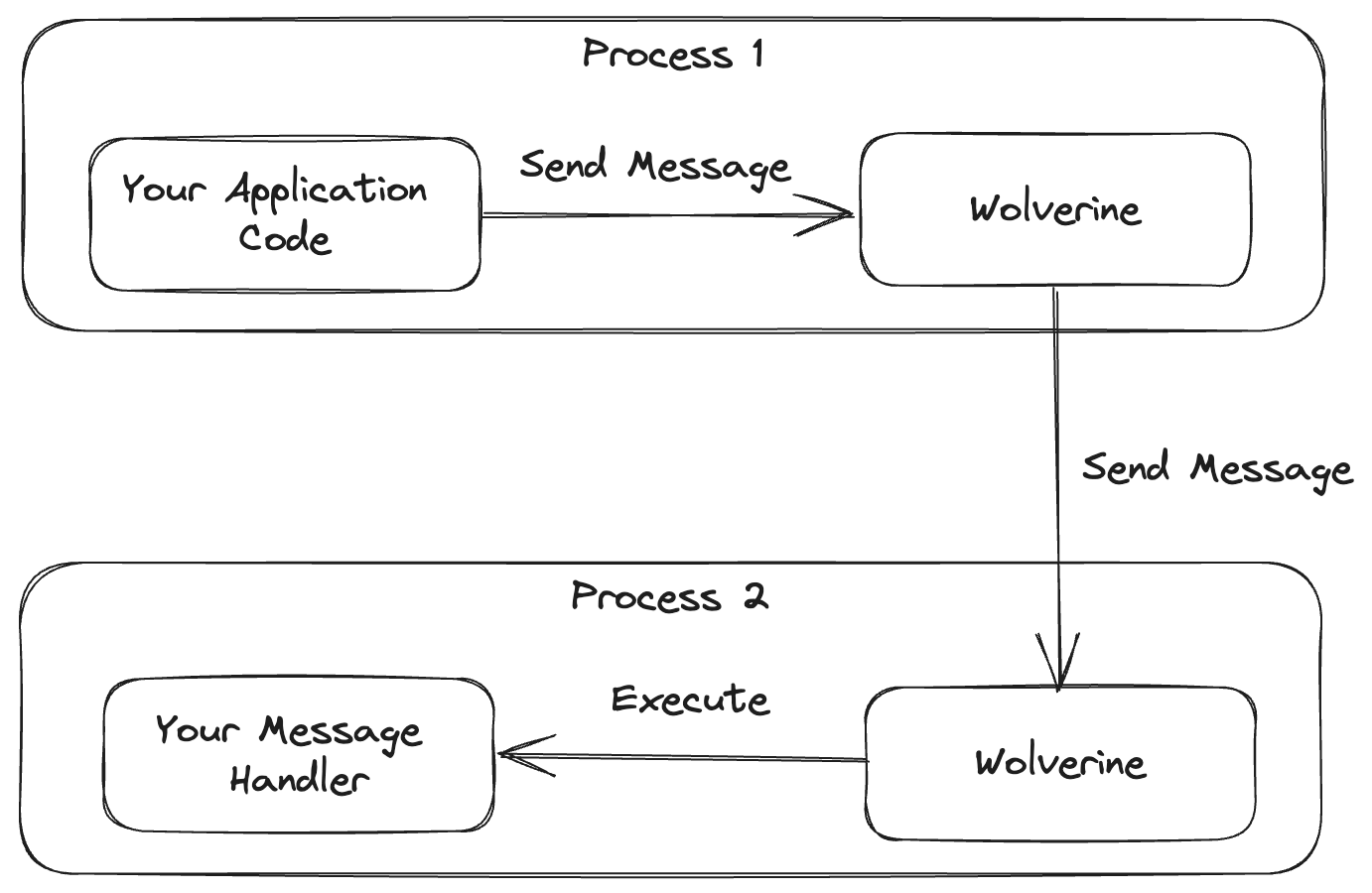

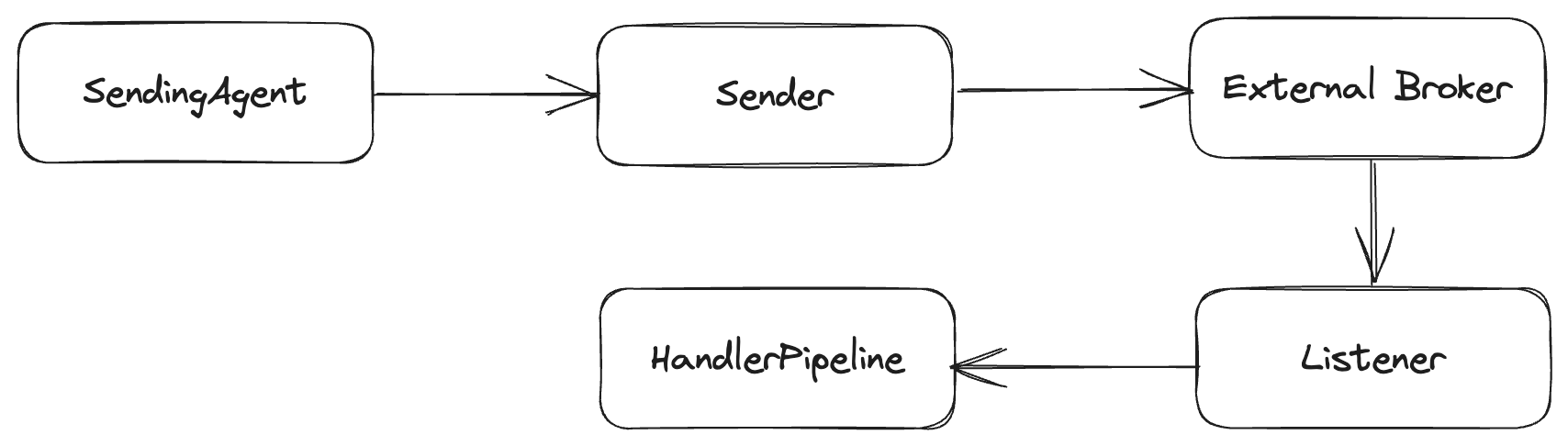

The other main usage of Wolverine is to send messages from your current process to another process through some kind of external transport like a Rabbit MQ/Azure Service Bus/Amazon SQS queue and have Wolverine execute that message in another process (or back to the original process):

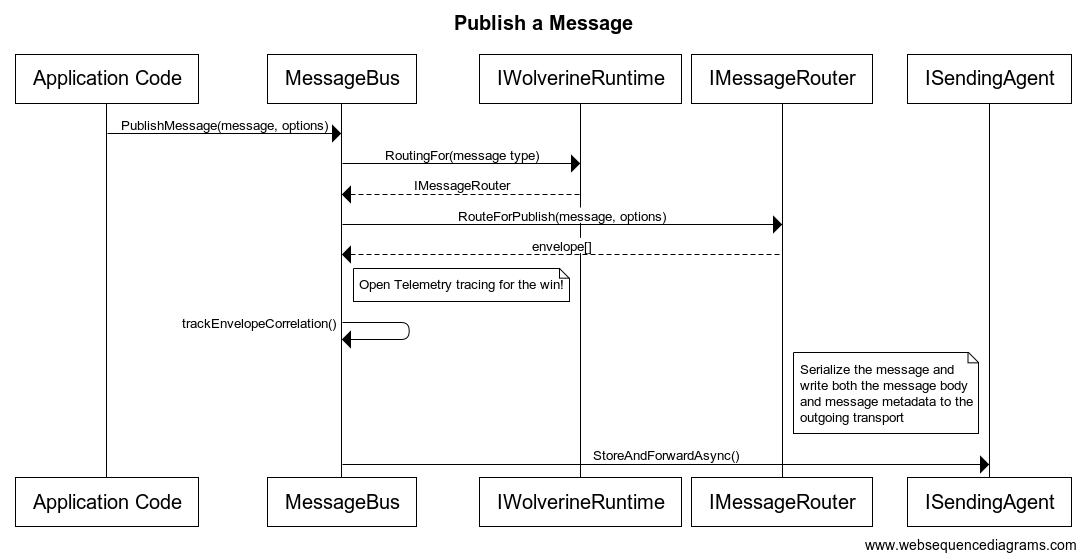

The internals of publishing a message are shown in this simplified sequence diagram:

Along the way, Wolverine has to:

- Serialize the message body

- Route the outgoing message to the proper subscriber(s)

- Utilize any publishing rules like "this message should be discarded after 10 seconds"

- Map the outgoing Wolverine

Enveloperepresentation of the message into whatever the underlying transport (Azure Service Bus et al.) uses - Actually invoke the actual messaging infrastructure to send out the message

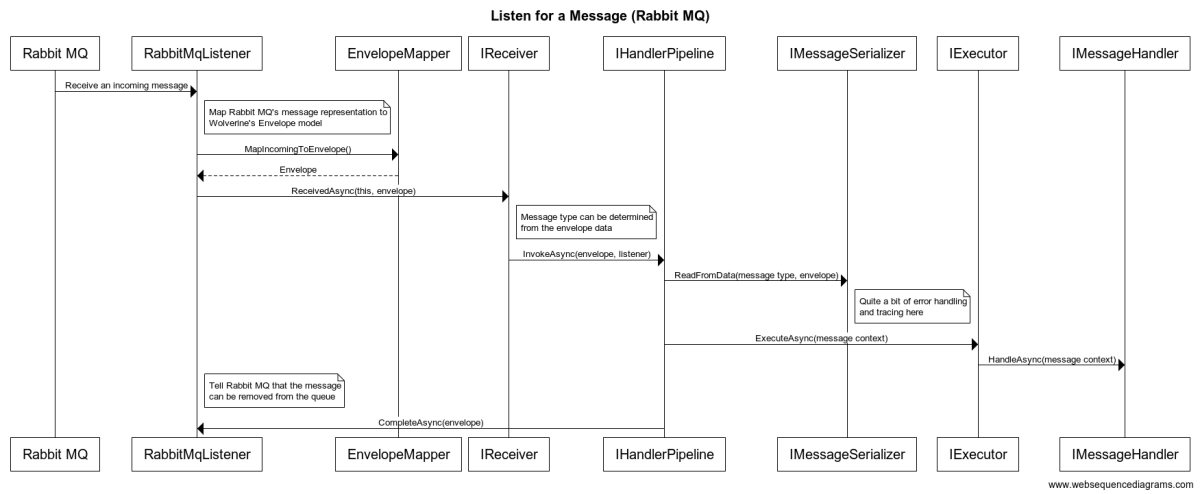

On the flip side, listening for a message follows this sequence shown for the "happy path" of receiving a message through Rabbit MQ:

During the listening process, Wolverine has to:

- Map the incoming Rabbit MQ message to Wolverine's own

Envelopestructure - Determine what the actual message type is based on the

Envelopedata - Find the correct executor strategy for the message type

- Deserialize the raw message data to the actual message body

- Call the inner message executor for that message type

- Carry out quite a bit of Open Telemetry activity tracing, report metrics, and just plain logging

- Evaluate any errors against the error handling policies of the application or the specific message type

Endpoint Types

INFO

Not all transports support all three types of endpoint modes, and will helpfully assert when you try to choose an invalid option.

Inline Endpoints

Wolverine endpoints come in three basic flavors, with the first being Inline endpoints:

// Configuring a Wolverine application to listen to

// an Azure Service Bus queue with the "Inline" mode

opts.ListenToAzureServiceBusQueue(queueName, q => q.Options.AutoDeleteOnIdle = 5.Minutes()).ProcessInline();With inline endpoints, as the name implies, calling IMessageBus.SendAsync() immediately sends the message to the external message broker. Likewise, messages received from an external message queue are processed inline before Wolverine acknowledges to the message broker that the message is received.

In the absence of a durable inbox/outbox, using inline endpoints is "safer" in terms of guaranteed delivery. As you might think, using inline agents can bottle neck the message processing, but that can be alleviated by opting into parallel listeners.

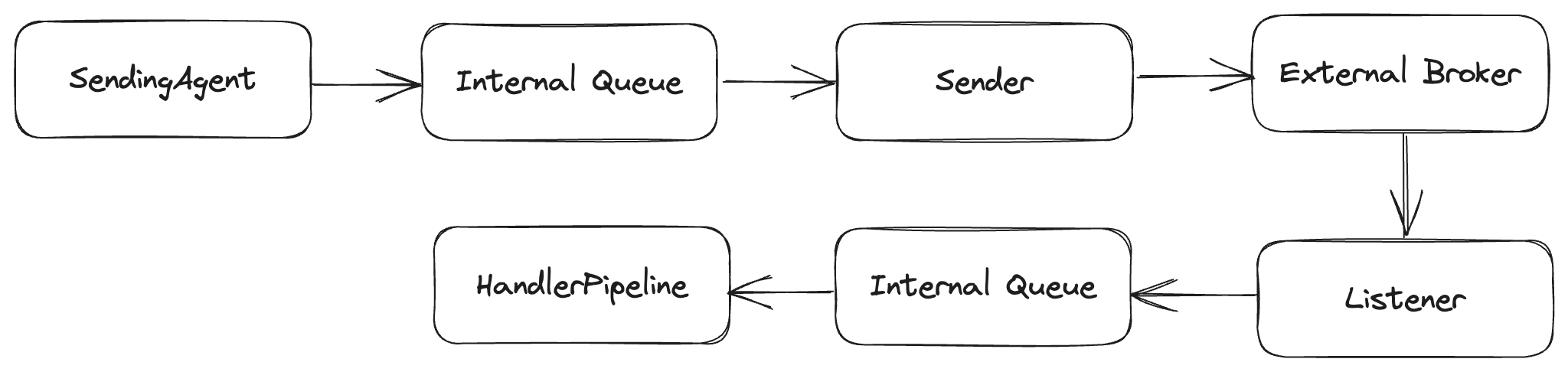

Buffered Endpoints

In the second Buffered option, messages are queued locally between the actual external broker and the Wolverine handlers or senders.

To opt into buffering, you use this syntax:

// I overrode the buffering limits just to show

// that they exist for "back pressure"

opts.ListenToAzureServiceBusQueue("incoming")

.BufferedInMemory(new BufferingLimits(1000, 200));At runtime, you have a local TPL Dataflow queue between the Wolverine callers and the broker:

On the listening side, buffered endpoints do support back pressure (of sorts) where Wolverine will stop the actual message listener if too many messages are queued in memory to avoid chewing up your application memory. In transports like Amazon SQS that only support batched message sending or receiving, Buffered is the default mode as that facilitates message batching.

Buffered message sending and receiving can lead to higher throughput, and should be considered for cases where messages are ephemeral or expire and throughput is more important than delivery guarantees. The downside is that messages in the in memory queues can be lost in the case of the application shutting down unexpectedly -- but Wolverine tries to "drain" the in memory queues on normal application shutdown.

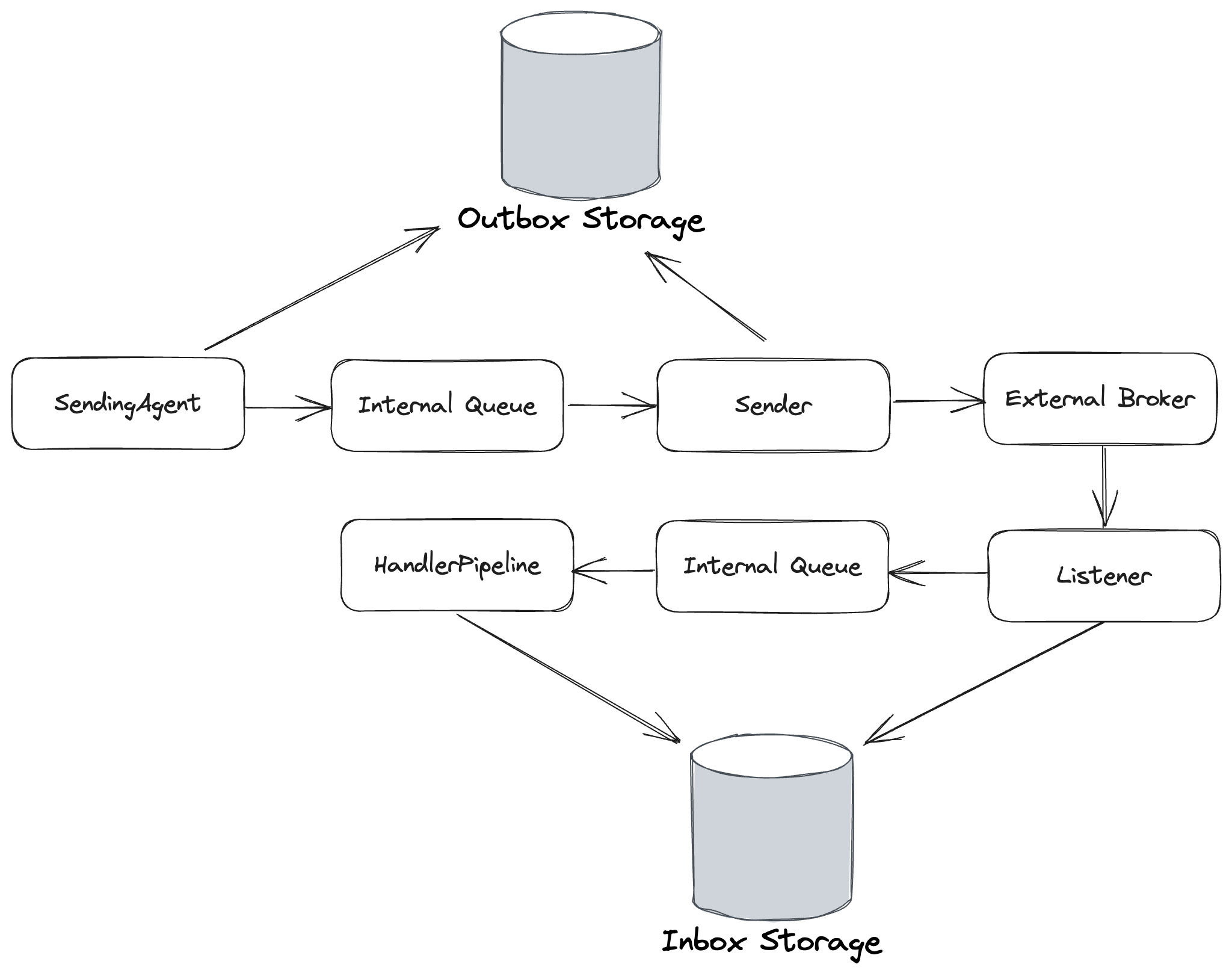

Durable Endpoints

Durable endpoints behave like buffered endpoints, but also use the durable inbox/outbox message storage to create much stronger guarantees about message delivery and processing. You will need to use Durable endpoints in order to truly take advantage of the persistent outbox mechanism in Wolverine. To opt into making an endpoint durable, use this syntax:

// I overrode the buffering limits just to show

// that they exist for "back pressure"

opts.ListenToAzureServiceBusQueue("incoming")

.UseDurableInbox(new BufferingLimits(1000, 200));

opts.PublishAllMessages().ToAzureServiceBusQueue("outgoing")

.UseDurableOutbox();Or use policies to do this in one fell swoop (which may not be what you actually want, but you could do this!):

opts.Policies.UseDurableOutboxOnAllSendingEndpoints();As shown below, the Durable endpoint option adds an extra step to the Buffered behavior to add database storage of the incoming and outgoing messages:

Outgoing messages are deleted in the durable outbox upon successful sending acknowledgements from the external broker. Likewise, incoming messages are also deleted from the durable inbox upon successful message execution.

The Durable endpoint option makes Wolverine's local queueing robust enough to use for cases where you need guaranteed processing of messages, but don't want to use an external broker.

How Wolverine Calls Your Message Handlers

Wolverine is a little different animal from the tools with similar features in the .NET ecosystem (pun intended:). Instead of the typical strategy of requiring you to implement an adapter interface of some sort in your code, Wolverine uses dynamically generated code to "weave" its internal adapter code and even middleware around your message handler code.

In ideal circumstances, Wolverine is able to completely remove the runtime usage of an IoC container for even better performance. The end result is a runtime pipeline that is able to accomplish its tasks with potentially much less performance overhead than comparable .NET frameworks that depend on adapter interfaces and copious runtime usage of IoC containers.

See Code Generation in Wolverine for much more information about this model and how it relates to the execution pipeline.

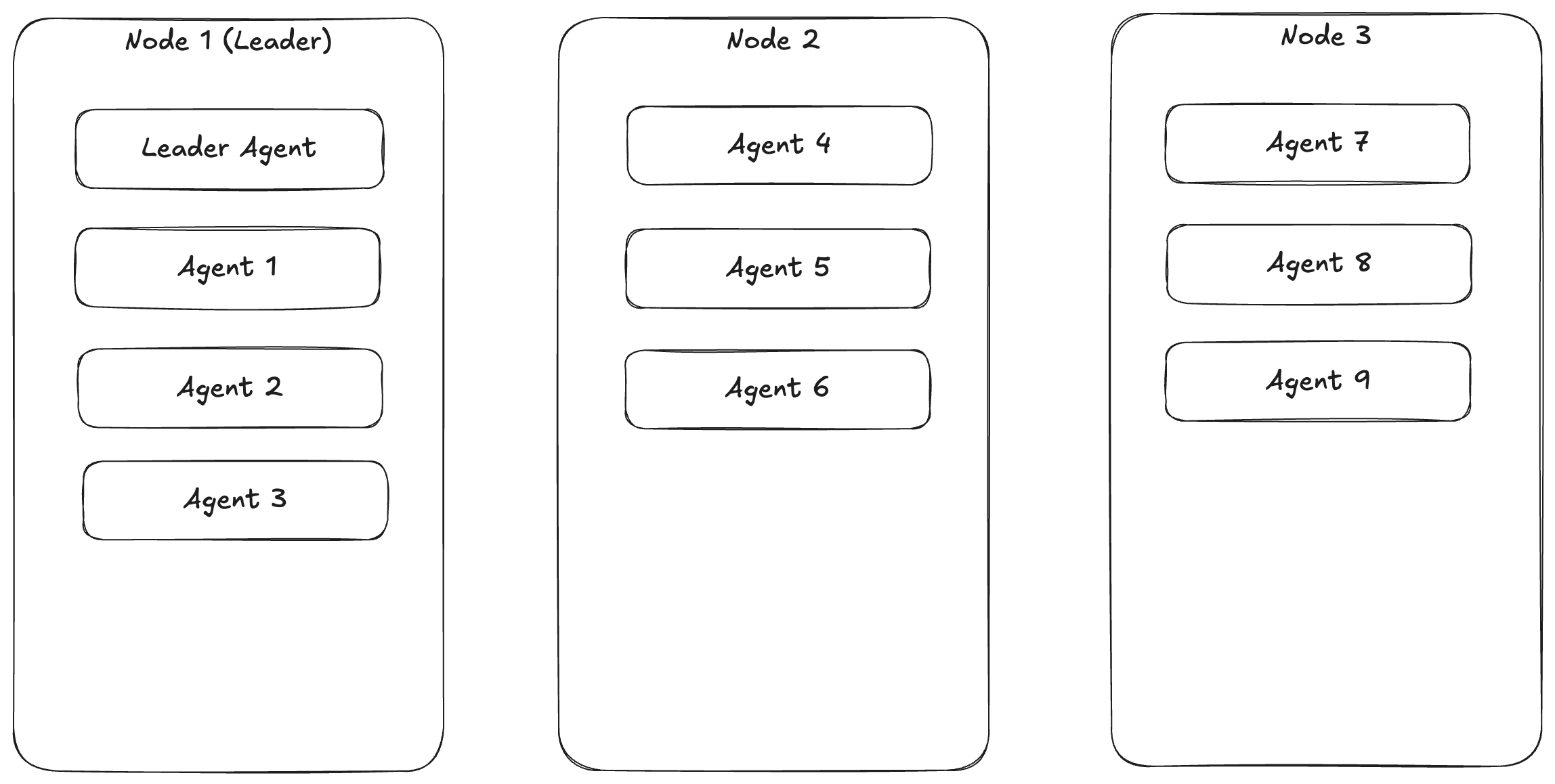

Nodes and Agents

Wolverine has some ability to distribute "sticky" or stateful work across running nodes in your application. To do so, Wolverine tracks the running "nodes" (just means an executing instance of your Wolverine application) and elects a single leader to distribute and assign "agents" to the running "nodes". Wolverine has built in health monitoring that can detect when any node is offline to redistribute working agents to other nodes. Wolverine is also able to "fail over" the leader assignment to a different node if the original leader is determined to be down. Likewise, Wolverine will redistribute running agent assignments when new nodes are brought online.

INFO

You will have to have some kind of durable message storage configured for your application for the leader election and agent assignments to function.

The stateful, running "agents" are exposed through an IAgent interface like so:

/// <summary>

/// Models a constantly running background process within a Wolverine

/// node cluster

/// </summary>

public interface IAgent : IHostedService // Standard .NET interface for background services

{

/// <summary>

/// Unique identification for this agent within the Wolverine system

/// </summary>

Uri Uri { get; }

// Not really used for anything real *yet*, but

// hopefully becomes something useful for CritterWatch

// health monitoring

AgentStatus Status { get; }

}/// <summary>

/// Models a constantly running background process within a Wolverine

/// node cluster

/// </summary>

public interface IAgent : IHostedService // Standard .NET interface for background services

{

/// <summary>

/// Unique identification for this agent within the Wolverine system

/// </summary>

Uri Uri { get; }

// Not really used for anything real *yet*, but

// hopefully becomes something useful for CritterWatch

// health monitoring

AgentStatus Status { get; }

}

public class CompositeAgent : IAgent

{

private readonly List<IAgent> _agents;

public Uri Uri { get; }

public CompositeAgent(Uri uri, IEnumerable<IAgent> agents)

{

Uri = uri;

_agents = agents.ToList();

}

public async Task StartAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

foreach (var agent in _agents)

{

await agent.StartAsync(cancellationToken);

}

Status = AgentStatus.Running;

}

public async Task StopAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

foreach (var agent in _agents)

{

await agent.StopAsync(cancellationToken);

}

Status = AgentStatus.Running ;

}

public AgentStatus Status { get; private set; } = AgentStatus.Stopped;

}With related groups of agents built and assigned by IoC-registered implementations of this interface:

/// <summary>

/// Pluggable model for managing the assignment and execution of stateful, "sticky"

/// background agents on the various nodes of a running Wolverine cluster

/// </summary>

public interface IAgentFamily

{

/// <summary>

/// Uri scheme for this family of agents

/// </summary>

string Scheme { get; }

/// <summary>

/// List of all the possible agents by their identity for this family of agents

/// </summary>

/// <returns></returns>

ValueTask<IReadOnlyList<Uri>> AllKnownAgentsAsync();

/// <summary>

/// Create or resolve the agent for this family

/// </summary>

/// <param name="uri"></param>

/// <param name="wolverineRuntime"></param>

/// <returns></returns>

ValueTask<IAgent> BuildAgentAsync(Uri uri, IWolverineRuntime wolverineRuntime);

/// <summary>

/// All supported agent uris by this node instance

/// </summary>

/// <returns></returns>

ValueTask<IReadOnlyList<Uri>> SupportedAgentsAsync();

/// <summary>

/// Assign agents to the currently running nodes when new nodes are detected or existing

/// nodes are deactivated

/// </summary>

/// <param name="assignments"></param>

/// <returns></returns>

ValueTask EvaluateAssignmentsAsync(AssignmentGrid assignments);

}Built in examples of the agent and agent family are:

- Wolverine's built-in durability agent to recover orphaned messages from nodes that are detected to be offline, with one agent per tenant database

- Wolverine uses the agent assignment for "exclusive" message listeners like the strictly ordered listener option

- The integrated Marten projection and subscription load distribution

IoC Container Integration

INFO

Wolverine has been tested with both the built in ServiceProvider and Lamar, which was originally built specifically to support what ended up becoming Wolverine. The previous limitation to only supporting Lamar was lifted in Wolverine 3.0.

Wolverine is a significantly different animal than other .NET frameworks, and uses the IoC container quite differently than most .NET application frameworks. For the most part, Wolverine is looking at the IoC container registrations and trying to generate code to mimic the IoC behavior in the message handler and HTTP endpoint adapters that Wolverine generates internally. The benefits of this model are:

- The pre-generated code can tell you a lot about how Wolverine is handling your code, including any registered middleware

- The fastest IoC container is no IoC container

- Less conditional logic at runtime

- Much slimmer exception stack traces when things inevitably go wrong. Wolverine's predecessor tool (FubuMVC) use nested objects created on every request or message for its middleware strategy, and the exception messages coming out of handler code could be epic with a lot of middleware active.

The downside is that Wolverine does not play well with the kind of runtime IoC tricks other frameworks rely on for passing state. For example, because Wolverine.HTTP does not use the ASP.Net Core request services to build endpoint types and its dependencies at runtime, it's a little clumsier to pass state from ASP.Net Core middleware written into scoped IoC services, with custom multi-tenancy approaches being the usual cause of this. Wolverine certainly has its own multi-tenancy support, and we don't think this is really a serious problem for most usages, but it has caused friction for some Wolverine users converting from other frameworks.